*Please note that the following post is from an essay that I wrote for my MSc Consciousness, Spirituality and Transpersonal Psychology- the writing style is academic and not as poetic as I would normally write my posts…but I thought it may be of interest!*

Evaluate the idea that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe.

The nature of consciousness remains one of the most profound and enduring mysteries within the fields of neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy (Wahbeh et al., 2020). According to Kuhn (2024), there are over 200 theories that attempt to demystify and explain the intrinsic properties of consciousness. Whilst there is a wide range of proposed theories, the prevailing paradigm is grounded in the physicalist assumption that matter is fundamental, positing that consciousness is either identical or reducible to neural processes in the brain (Beauregard et al., 2018). However, growing interest in alternative frameworks challenges this view, suggesting that consciousness may be more fundamental than matter itself (Wahbeh et al., 2022). This essay intends to evaluate the concept that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe by examining the limitations of the dominant physicalist paradigm, particularly the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness and the prevalence of near-death and out-of-body experiences. I will also explore alternative theories, including panpsychism, cosmopsychism, analytical idealism, alongside my personal experience of Body-Mind centering and non-dual Shaiva Tantra. Finally, the broader implications of regarding consciousness as a universal property will be discussed, illustrating how this perspective reshapes our understanding of reality and our place within it.

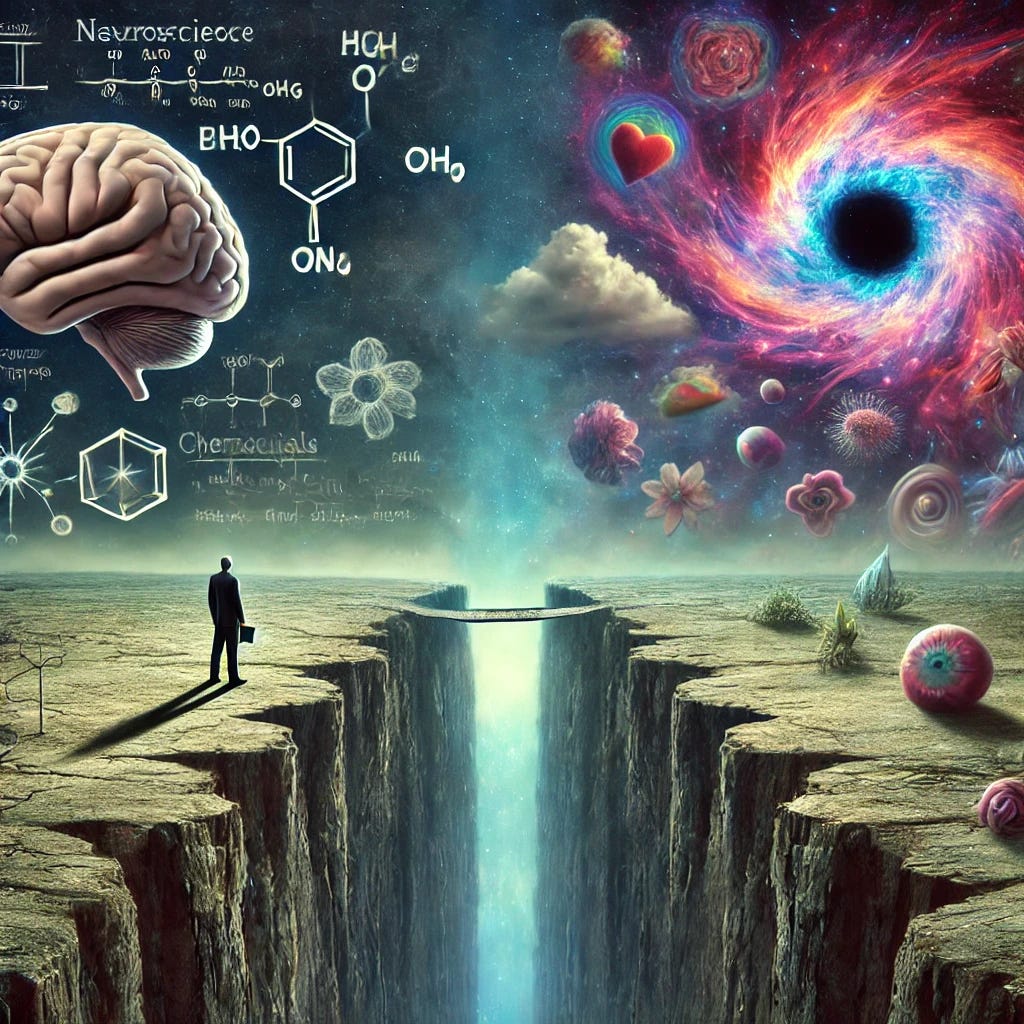

Lost in the Explanatory Gap: A Chasm Without a Bridge

In order to explore the notion that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe, and, thus, more fundamental than matter, it is first important to address the primary criticisms of the physicalist framework. As Koch (2024) highlights, there are a wide range of diverse theories of consciousness that could be defined under the physicalist umbrella. However, despite differing theories, a common thread between them is the assumption that everything in our reality is constituted of and can be explained through physical properties (Goff et al. 2017). From this view, consciousness is considered an emergent property from the chemical and electrical processes in the brain; it is just what the brain does (Beauregard et al., 2018). In order for this perspective to be validated, it is essential for the proponents of these theories to identify the ‘neural correlates of consciousness’ (NCCs) (Alkire & Miller, 2005). The search for NCCs can be defined as seeking to measure and identify the “minimum neuronal mechanisms jointly sufficient for any one specific conscious experience” (Koch et al., 2016, p. 308). This research hopes that, with more advanced brain imaging techniques, the mystery of which specific neural processes give rise to subjective phenomenal experience will be clarified (Keppler, 2020).

However, there are many scholars who suggest that the search for NCCs will remain fruitless, as the supporters of physicalist theories are simply looking in the wrong place (Kastrup, 2020; Levine, 1983; Wahbeh et al., 2022). Physicalism attempts to explain phenomenological experiences, or qualia, through a direct comparison to specific neural mechanisms in the brain. Proponents of strong emergentism, like Tononi (2012), argue that while consciousness emerges from complex neural interactions, it is still fundamentally rooted in physical processes. Yet, it can be argued that these physical processes provide little insight into the subjective qualities of experience; what it is like to listen to a symphony, watch a sunset, or taste the sweetness of strawberries in summer. There is seemingly an insurmountable chasm between the physical processes of the brain and subjective experience, which is known as the ‘explanatory gap’ (Levine, 1983) or the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness (Chalmers, 1995). The ‘hard problem’ presents a considerable challenge to the validity of physicalism and the proposition that consciousness can be reduced to quantifiable parts. Despite rigorous and extensive efforts to attempt to validate physicalism through the search for NCC’s, it can be argued that “none of these theories have completely and convincingly explained the nature of consciousness” (Wahbeh et al., 2022, p. 3).

Further to the primary criticism of physicalism of the unavoidable ‘hard problem’ of consciousness, there is also a body of research that indicates that individuals can sometimes receive meaningful information through other sense faculties and, thus, conscious experience has the potential to exist outside of habitual space-time constraints (Beauregard et al., 2014). The field of psi phenomena, most notably near-death experiences (NDEs) and out-of-body experiences (OBEs), presents a strong counter argument to physicalism. From the physicalist view, it would seem logical to assert that during events that cause brain activity to be impaired, there should be little or no experience of phenomenological consciousness. However, a substantial body of evidence suggests that some individuals who experience NDEs can exhibit lucid consciousness and clear reasoning, even with reduced brain function (Parnia et al., 2001).

Despite compelling evidence supporting the occurrence of NDEs and OBEs, some physicalists, such as Greyson (2003), argue that these experiences can be explained by neurological phenomena, such as brain hypoxia. According to this stance, the mind can continue to exhibit normal function during the cessation of certain neural processes, which can explain lucid experiences even when brain activity is impaired (Greyson, 2003). However, this explanation fails to account for the verifiable details provided by individuals during OBEs, such as descriptions of events that occurred out of direct line of sight, which have been corroborated by independent witnesses (Beauregard et al., 2018). The consistency and reliability of such data challenges dominant physicalist paradigms and dismissing these experiences as legitimate may reflect a bias against theories that question the physicalist perspective (Butzer, 2020). Given their prevalence, these events should not be viewed as mere exceptions to the physicalist assumptions of reality but rather as “indications of the need for a broader explanatory framework that cannot be predicated exclusively on materialism” (Beauregard et al., 2014, p. 2). The challenges faced by physicalism, including the ‘hard problem of consciousness’ and the phenomenon of NDEs and OBEs, suggest that consciousness may not be entirely derivative of brain function. Therefore, it has become clear that phenomenological consciousness may not be fully explained by material processes, which raises the question: Could it be a fundamental aspect of reality itself? Alternative frameworks that more fully explore this question are panpsychism and cosmopsychism.

From Atoms to Awareness: A Mind-Bending Perspective

In the pursuit to explain consciousness beyond the physicalist framework, panpsychism has emerged as a leading contender (Medhananda, 2024). This ontological perspective proposes a potential solution to the limitations of the physicalist explanation of consciousness by asserting that it is a fundamental property of the universe (Goff et al., 2017). According to panpsychism, all matter, whether river, rocks, atoms or skin cells, possesses some form of subjective phenomenological awareness (Blackmore & Troscianko, 2018). According to this ontology, consciousness is an inherent property in all physical entities because all ‘ultimates’ of energy-matter have phenomenal experience. In other words, wherever matter and energy exist, there is also some basic form of consciousness (Kuhn, 2024).

While the roots of this ontology are found in both Eastern and Western traditions, its growing popularity can be largely attributed to its potential to address the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness (Medhananda, 2024). Unlike physicalism, which seeks to explain qualitative experiences using the language of the quantitative, panpsychism attempts to uncover the intrinsic nature of what consciousness is, as opposed to describing what it does. As Eddington (1920) aptly noted, “Physics is the knowledge of structural form, and not knowledge of content. All through the physical world runs that unknown content, which must surely be the stuff of our consciousness” (p. 200). By focusing on the intrinsic subjective qualities of consciousness, panpsychism offers an elegant solution to the ‘hard problem’, as it posits that consciousness is a fundamental feature of reality, eliminating the need to explain how it emerges from non-conscious matter. It reconciles the laws of the physical world with the subjective, qualitative aspects of experience, thereby making space for consciousness within the material reality.

Alongside theoretical support for panpsychism, personal experience can also serve as compelling evidence to strengthen the notion that consciousness exists at all levels of matter. Through my practice of Body-Mind centering, I have had the profound experience of feeling consciousness not just in my mind, but within the very cells of my body. Hartley (1995) describes this practice as a method to come into direct contact with our various corporal systems and “initiate movement from them so that each of their qualities becomes available to us as a means of expression” (p. xxxii). In moments of practice, I have directly experienced the intelligence of my cells, where my boundaries are that of the cell wall, where my fullness is cellular liquid, and I am nothing but the inherent desire of life force to express itself (Weber, 2017). This subjective experience aligns with the panpsychist understanding that consciousness is not restricted to the brain but is inherent in all physical entities. Such a direct and embodied experience challenges physicalism, and points towards and more integrated understanding of consciousness that permeates all aspects of existence.

Despite the appeal of panpsychism, it faces significant criticisms, the most notable being the ‘combination problem’ (Medhananda, 2024). Critics, such as Kuhn (2024), argue that the leap from micro-level consciousness to macro-level experience is implausible. Further to this, I may wonder if my subjective experience of the aliveness and intelligence of my skin cells is legitimate, why am I not overwhelmed by millions of separate voices and experiences? While this is a valid critique, Goff (2017) counters that consciousness may integrate at higher levels of complexity to form individual subjective experience, just as individual cells combine to form a coherent organism. This idea, while still developing, offers a promising path to addressing the challenge of the ‘combination problem’.

Waves in the Cosmic Mind: Ripples of Universal Awareness

Like physicalism, panpsychism, is expressed in various forms and interpretations (Kuhn, 2024). One such variant, cosmopsychism, offers a potential solution to the ‘combination problem’. Medhananda (2024) explains that due to the challenges posed by the ‘combination problem’, some contemporary philosophers have moved away from panpsychism “in favour of cosmopsychism, the view that human and non-human animal consciousness derives from ‘cosmic consciousness’, a single, all-pervading consciousness” (p. 115). This view presents an inverse ontology to panpsychism; instead of the macrocosm being grounded in the microcosm, the small is grounded in the vast. Goff et al. (2022) argue that in following this argument to its logical conclusion, there is only one fundamental thing: the universe. Keppler (2020) further elaborates on cosmopsychism, describing universal consciousness as “a shapeless, undifferentiated ocean of consciousness in the basic structure of which all shades of phenomenal awareness are inherent” (p. 19). Keppler (2020) also asserts that matter acquires phenomenological properties when it encounters the cosmic field of consciousness, extracting “a subset of phenomenal tones from the spectrum of all phenomenal tones potentially present in the field” (p. 19).

In this context, the idea that the universe itself is conscious offers a way to avoid the ‘combination problem’, by starting with a fundamental, universal consciousness, from which individual minds derive, rather than needing to combine smaller conscious units into a larger one. However, this theory, introduces new challenge; the ‘individuation problem’. How does one universal consciousness individuate into the conscious experience of individuals? To address this critique, Medhananda (2024) defends cosmopsychism by suggesting that cosmic consciousness individuates through a “dual process of ‘self-limitation’ and ‘exclusive concentration’” (p. 124). According to this position, cosmic consciousness can limit itself to multiple points of awareness simultaneously, each experiencing its own individuality, while remaining connected to the larger body of consciousness. The analogy of a wave in the ocean illustrates this idea; though the wave is distinct in its finite form, it remains, fundamentally, part of the ocean. As Saraswati (2017) expresses, “We're more like waves arising from an ocean. A wave is dependent on the ocean. In fact, a wave is ocean” (p. 40).

To further substantiate the idea that consciousness is the fundamental property of reality, and that cosmic consciousness has the capacity to individuate into multiple distinct forms of experience, we can examine the theory of analytical idealism, as proposed by Kastrup (2018). Kastrup (2018) strengthens the argument that the ‘individuation problem’ can be solved by suggesting that cosmic consciousness contracts itself into discrete loci of consciousness, known as ‘alters’, through a process of dissociation (Popovič, 2023). Kastrup (2018) draws on the lived experience of dissociative identity disorder (DID) to argue that, like individuals who have DID, cosmic consciousness can individuate into separate conscious experiences, each bound by its own boundaries but still connected to the whole. Popovič (2023) argues that the existence of DID supports Kastrup’s theory by showing how consciousness can simultaneously remain individual yet interconnected.

Critics may argue that this theory cannot be verified through conventional scientific methods, such as quantitative measurement. However, emerging evidence suggests that aspects of cosmopsychism may be integrated into established scientific frameworks. For instance, Keppler (2020), posits that stochastic electrodynamics (SED) “commends itself as a promising approach for the integration of consciousness into a coherent theoretical framework” (p. 21). More importantly, it can be argued that the challenge is not to fit alternative theories of consciousness into the Western framework of empirical verification, but to expand our understanding of what constitutes as valid evidence. As Hunter (2024) suggests, the scope of evidence should encompass more than just the empirical and integrate other ways of knowing, including the subjective, first-person experience. There are numerous first-person accounts of mystical experiences that support the notion of universal consciousness and Medhananda (2024) further strengthens their validity by arguing that “mystical testimony is an important source of evidence that philosophers ought to take seriously” (p. 118).

My personal relationship with the philosophy of non-dual Shaiva Tantra (NST) offers further support for the cosmopsychist understanding of a cosmic consciousness. From the philosophy of NST, everything in existence is made up of one vast field of energy, known as the Light of Awareness (Wallis, 2012, p. 57). Further to this, Wallis (2012) asserts that, from this view, “sentient beings like us are simply nodal points of self-awareness, recursive movements of energy in an otherwise undifferentiated dynamic field” (p. 58). This philosophical interpretation challenges the critique of the ‘individuation problem’ of cosmopsychism by explaining that the Light of Awareness freely contracts “the scope of identity to a particular individual domain of experience” (Williams & Woollacott, p. 3). According to NST, the Light of Awareness contracts itself into individual expression to experience the unfolding of self in a multitude of lenses; to know Herself more deeply. As Wallis (2012) expresses “indeed, you are the very means by which She knows Herself” (p. 56).

Through my exploration of NST, I have encountered moments where the boundaries between my individual self and the larger universe dissolves. In these moments, I am no longer only connected to my personal experiences but am connected to the Light of Awareness. This experience of interconnectedness and the dissolution of my subjective experience supports the cosmopsychist view, offering a personal validation of the notion that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe. The idea that my subjective awareness is not isolated but is instead a reflection of the Light of Awareness strengthens the cosmopsychist argument against the physicalist paradigm, which cannot fully explain this direct experience of interconnectedness.

Conclusion

The quest to demystify the nature of consciousness remains one of the most profound philosophical and scientific inquiries. Throughout this essay, I have examined the limitations of physicalism and challenged the assertion that consciousness is solely an emergent property of neural activity. Further to this, explorations of phenomena such as NDEs and OBEs, alongside personal accounts of interconnectedness to the Light of Awareness, suggest that phenomenological consciousness may extend beyond the brain (Beauregard et al., 2014). As a result, alternative frameworks, such as panpsychism and cosmopsychism, have emerged as compelling contenders for explaining consciousness as a fundamental property of the universe.

Panpsychism argues that consciousness is an inherent property of matter, while cosmopsychism posits that our individual subjective experience of consciousness is derivative of a cosmic consciousness. The latter, strengthened by analytical idealism and the philosophy of NST, provides coherent resolutions to the ‘combination problem’ by asserting that cosmic consciousness individuates into distinct loci of awareness. Through my own experiences with Body-Mind centering and NST, I have found personal resonance with both perspectives; the former speaks to the embodied cellular nature of consciousness, while the latter highlights the interconnectedness of a cosmic consciousness.

However, this dual experience presents a paradox. At first glance, these positions may seem contradictory; one asserting consciousness as inherent to matter, the other as stemming from a universal source. This paradox, however, does not undermine the validity of these personal experiences as a source of evidence. Medhananda (2024) further suggests that these apparently conflicting testaments can, in fact, be seen as complementary, when appealing to the parable of the blind man and the elephant to clarify the harmonizing viewpoints. Each perspective, whether embodied in the cells or universal in the cosmos, reveals a different angle of the same underlying truth and strengthens the position that consciousness is not confined to the brain. In this way, the paradox becomes a reflection of the complexity and richness of consciousness, suggesting that it is both inherently tied to the material world but also an expression of a larger, universal consciousness.

Ultimately, the notion that consciousness is an inherent property of the universe has profound implications for our understanding of reality, dissolving the rigid boundaries between mind and matter. This perspective not only challenges the prevailing physicalist paradigm but also invites a more integrated, holistic view of existence that acknowledges both scientific inquiry and subjective experience. As Beauregard (2018) suggests, recognising consciousness as an inherent property of the universe fosters values such as “compassion, respect, and peace because it promotes an awareness of our interconnection” (p. 45). By seeing ourselves as expressions of a shared consciousness, we may cultivate a greater sense of unity, not only with each other but with the cosmos itself.

References

Alkire, M. T., & Miller, J. (2005). General anesthesia and the neural correlates of consciousness. Progress in brain research, 150, 229-597.

Beauregard, M., Schwartz, G. E., Miller, L., Dossey, L., Moreira-Almeida, A., Schlitz, M., Sheldrake, R., & Tart, C. (2014). Manifesto for a post-materialist science. EXPLORE, 10(5), 272–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2014.06.008

Beauregard, M., Trent, N. L., & Schwartz, G. E. (2018). Toward a postmaterialist psychology: Theory, research, and applications. New Ideas in Psychology, 50, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.02.004

Blackmore, S., & Troscianko, E. (2018). Consciousness: An introduction (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Butzer, B. (2020). Bias in the evaluation of psychology studies: A comparison of parapsychology versus neuroscience. Explore (New York, N.Y.), 16(6), 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2019.12.010

Chalmers, D. J. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2(3), 200–219.

Eddington, A. S. (1920). Space, Time And Gravitation: An Outline Of The General Relativity Theory. Kessinger Publishing, LLC.

Goff, P., Seager, W., & Allen-Hermanson, S. (2017, July 18). Panpsychism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/panpsychism/#DefiPanp

Goff, P., Seager, W., & Allen-Hermanson, S. (2022). Panpsychism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Summer 2022 Edition).

Greyson, B. (2003). The physiology of near-death experiences. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 22(3), 141-153. https://doi.org/10.17514/JNDS-2003-22-3-p141-153

Hartley, L. (1995). Wisdom of the body moving: An introduction to body-mind centering. North Atlantic Books.

Hunter, D. (2024). “Cross-cultural perspectives on mind, self, person, and consciousness”. International Journal of Consciousness Studies, 31(1), 9-17.

Kastrup, B. (2018). The universe in consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 25(5-6), 125-155.

Kastrup, B. (2020, June 9). Further reply to Philip Goff. Metaphysical Speculations. https://www.bernardokastrup.com/2020/06/further-reply-to-philip-goff.html

Keppler, J., & Shani, I. (2020). Cosmopsychism and consciousness research: A fresh view on the causal mechanisms underlying phenomenal states. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 371. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00371

Koch, C., Massimini, M., Boly, M., & Tononi, G. (2016). Neural correlates of consciousness: Progress and problems. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(5), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.22

Koch, C. (2020). The feeling of life itself: Why consciousness is widespread but can’t be computed (Illustrated ed.).MIT Press.

Kuhn, R. L. (2024). A landscape of consciousness: Toward a taxonomy of explanations and implications. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 190, 28–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2023.12.003

Levine, J. (1983). Materialism and phenomenal properties: the explanatory gap. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 64(4), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0114.1983.tb00207

Medhananda, S. (2024). Can consciousness have blind spots? Journal of Consciousness Studies, 31(9-10), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.53765/20512201.31.9.113

Parnia, S., Waller, D. G., Yeates, R., & Fenwick, P. (2001). A qualitative and quantitative study of the incidence, features, and aetiology of near-death experiences in cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation, 48(2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9572(00)00328-2

Popovič, J. (2023). Conception of human being in analytical idealism: How human and cosmos are interlinked through consciousness: Postdisciplinary humanities & social sciences quarterly. Human Affairs, 33(2), 224-236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/humaff-2022-1013

Saraswati, S. (2017). Nine poisons, nine medicines, nine fruits: A spiritual guide to self-diagnosis and healing. Kali Durga Press.

Tononi, G. (2012). Integrated information theory of consciousness: An updated account. Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 150(1), 56-90. https://doi.org/10.4449/aib.v150i1.1406

Wallis, C. (2012). Tantra illuminated: The philosophy, history, and practice of a timeless tradition. Mattamayūra Press.

Wahbeh, H., Radin, D., Cannard, C., & Delorme, A. (2022). What if consciousness is not an emergent property of the brain? Observational and empirical challenges to materialistic models. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 955594. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.955594

Weber, A. (2017). Matter and desire: An erotic ecology. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Williams, B., & Woollacott, M. H. (2021). Conceptual cognition and awakening: Insights from non-dual Śaivism and neuroscience. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 53(2), 117-136.

Thank you so much Phil, this really means a lot! My absolute dream is to be a lecturer in the field of transpersonal psychology and spirituality and do my tarot stuff; so this feedback is so amazing 😍 yes, absolutely, language is so important when discussing our subjective experience - there's loads of research!

Thank you Takim! I loved how you spoke about self as an illusion, which I'm still not sure that I'd be ready to let go selfishly- even though I practice a non-dual Tantric philosophy.

I found your argument against the combination problem interesting and need to sit with it all a bit more...if you have any further literature that you can point me towards reading, I'd love that!

Also, I must mention that, as this was an academic essay, I did need to provide a balanced account of the current theories and their criticisms within the field- so not all of the criticisms fully reflect my thoughts on the topic ✨

Let me sit with all these points a bit longer, you've sparked some interesting questions!